I begin this text about the artwork of Carlo Buzzi with a technical-media note: he has been one of the first Italian artists who have promoted the information and documentation of their work on a website; since the beginning of 90s, when the online presence still was counted, he was already prepared with a well-structured and exaustive documentation on the net. Open to the world beyond the small global village of contemporary art. To be opened up to an eterogeneous public has always been his care, although in perspective, as we will see, he isn’t so interested in the public, only as much as he needs to impose it his vision, also characterized by the catch of the evasive glance of the passenger, who is looking with the corner of his eye for something keeping close to the walls.

In 1995 he had got his “gate” on the net, a virtual gallery, they used to say so, one of the first online specific sites dedicated to contemporary art, mainly to offer evidence of his artistic activity and, in the context of a participatory and shared dimension, to insert the biographic profiles and artworks of his artist-friends related to him by collaboration and respect. The site had a poetic name, he has given it the name of a flower: “Margherita”.

The predisposition to believe in the totally innovative world of the web was possible for him thanks to his knowhow and implications in the IT world and to the visionary and future incentive of considering the Internet absolutely functional to document such a work as his own, conceived for the media and the street.

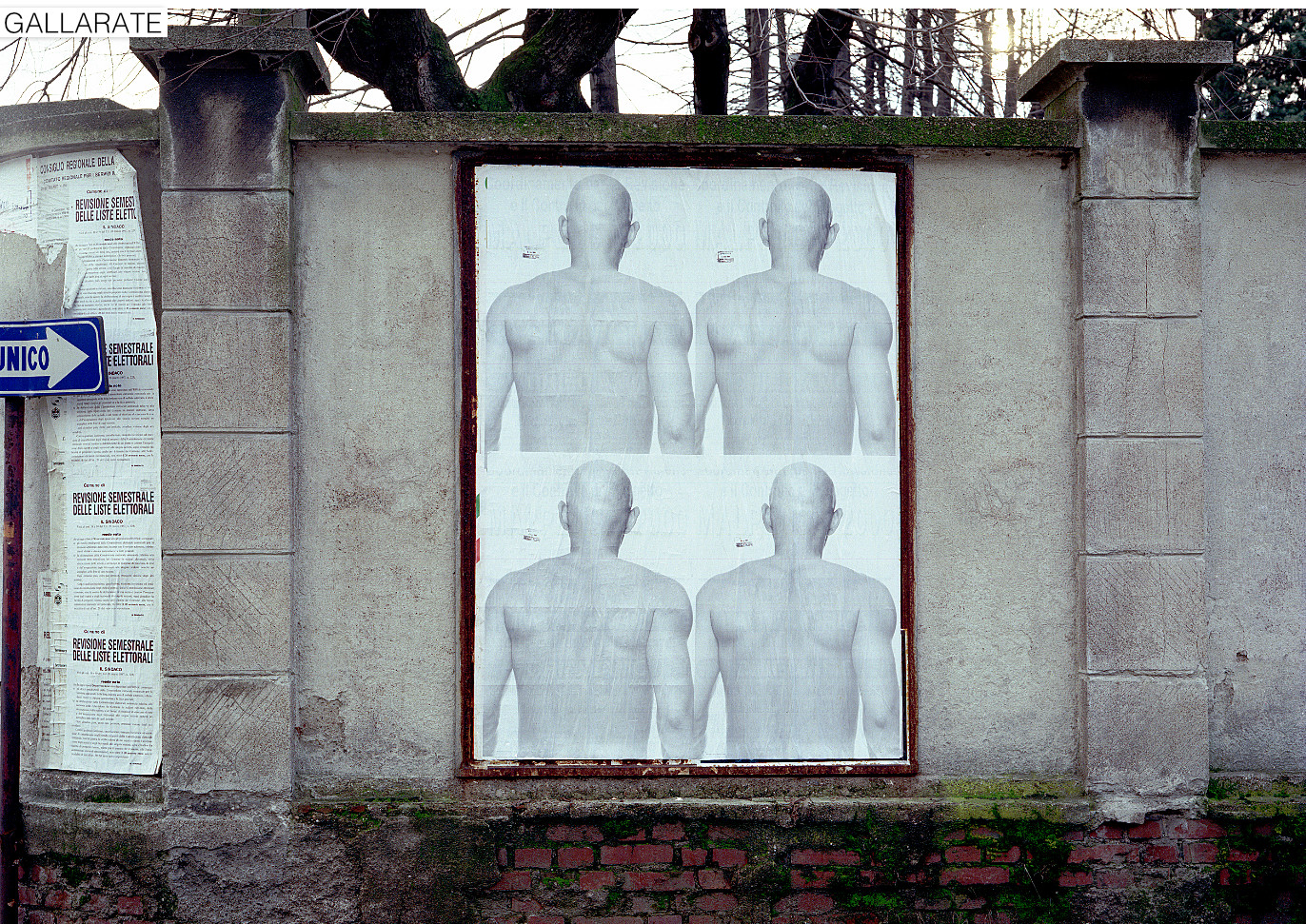

My first memory of him was the unexpected and misterious encounter with a page, appeared on an issue of the Flashart magazine in 1990. An ad it seemed, but in the immediate moment there weren’t pretexts that made me sure it was an advertisement, that has been realized, I discovered later, with the collaboration of Luciano Inga-Pin. An ambiguous communication at a first sight, which pointed out a phantomatic exhibition, perhaps an exhibition… but only because of the name of Picasso in the title, which combined in a provocatory way the artist’s name with the image of a shoddy toilet’s brush and a synthetic hour. Though adopting a system of visual codes close to advertising, with headline, body copy, attach, base line, etc.. the result was a total enigma. This was the first so-called “public” operation. Then he went out from the magazine pages to enter directly the streets, over there, vertically on the walls. Buzzi realized soon that the intrusion into an art magazine was so suspecting, implicit and related to the art system, that it was easy to conclude it was an artist’s intervention, even if anonymous and hidden, because his operation was anyway spreading and moving around the tangles of a system he wanted to overcome. The natural solution, the solving theme that would have distinguished him, he would discover it some months later, when he‘d move his communication directly “into the street”, aiming at a deeper relationship with the location system of mass communication; particularly, with the trade circuit of the public billposting. In this way, he has chosen to share its operativity, partly its canon and especially its locations, focusing on the differences between his operations, connotated by a rare radicality, and the advertisements, whose purpose is obviously the trade of a product, and looking for, among the bare wrinkles of an established coercive message, a subtle short-circuit between its “mute” images and the alluring spots of the advertising posters. Adbursting: anti-advertisement, I would say.

He operates with the media of billposting, historically connotated by an own peculiarity, to go through the paths of the paradox, approaching and getting close to the conventional and disciplinate messages of the operative consumerism (exactly as these “integrated antagonists”, he reserves the spaces of public domain), trying to arrange a coverage of posters in the assigned streets, that is plausible and powerful enough to obtain a certain visibility all over the city. The choice to compare himself with the urban advertising system doesn’t come from a specific interest in this kind of communication, but rather from the need to overcome the limits of the art world (he considers them narrow and dated, historically anachronistic), to overpass the spaces of the assigned exhibit locations and renovate the circuit artist-work-critic-galerist-museum, in search of outer, different and obviously not whitecube spaces (his operation besides entails a process and historicization of the artwork that he considers the return into the context).

It’s clear that the “conventional” ad aims to promote a product and produces trade, that it’s predisposed to a clarity and specificity made to catch a definite target with a clear, effective and “comforting” message towards the public. Here is it, the operation of Buzzi is dispensed with this purpose and rather re-calibrated on the basis of poetic and aesthetic rules.

The occasional viewer who finds himself observing one of his posters, remains free from references and so he is driven to an unreleased and unespected reflection, far from the normal reading conventions of the images in the urban space; this viewer isn’t considered as a consumer, Buzzi doesn’t conceive in him a model addressee, nore a target. His general addressee is inducted to experiment in the everyday context a strange kind of sensorial and emotional confusion, and immediately later, when the question becomes urgent, intellectual too. The adopted language, we should not forget, is always the art.

It’s important to underline that Buzzi pays – depending on the municipal fee in force – for the spaces he uses. Buying, as an advertising agency, the space needed for the construction and put-on-view of the work, he acts as a specialized operator, and so he uses within strict rules the concreteness of the operative system and commercial and social rules in support to his expressive aims. The number of exposed papers, for example in a standard format, is comparable – even if in minimum terms – to an advertising commercial campaign for any company or product but, according to him – in order to his poetics of being among things – the “place” is more signicative than the content. The repetition of his images inside the advertising circuit is systematic and regulated, but it’s also a break, an anacoluthon that in some way disturbs the specificity of the other billposting campaigns messages.

Those square metres of walls that will support his being in the world, and here I mean the normal, common, usual world of people, with the people walks, the rapid glances of drivers, the urgency, the lack of time and all the busy mourning of our civilization: with or without the public, the artistic operations of Buzzi are square metres of pure question about our lives’ destiny.

What makes Buzzi’s art „Public art“? Buzzi often remembers us in clear letters that what makes „public art“ is the fact to have grown up a „public consciousness“. I like this idea of his consciousness, over there attached on the walls… that is then a stance, a precise choice of the battlefield.

Evidence of this is the orderliness of the operation he has been managing from 1990 till now. There’s no improvisation, as it was often revealed either in performances following one another during these years, showing off the public art label, in extemporary works of artists momentarily dedicating to the „wall“, or in a pseudo-generic art made in the public, only because in the open space or in direct contact with the urban space.

The fact that there are people in the city and so his posters could loom over them isn’t neither primary nor determinant, as much as a spectator with visual anarchy, who can be either accomplice of the work, ignorant victim or uninterested public. In the end what does Buzzi make of the public? He apply a concept strategy that moves the work/operation from the art context into the street (at this point, as Buzzi often underlines when he tells about his artworks, „even if the city were empty anything wouldn’t have changed about the sense of my strategy“). This is the topic and his magnificent contradictory nature.

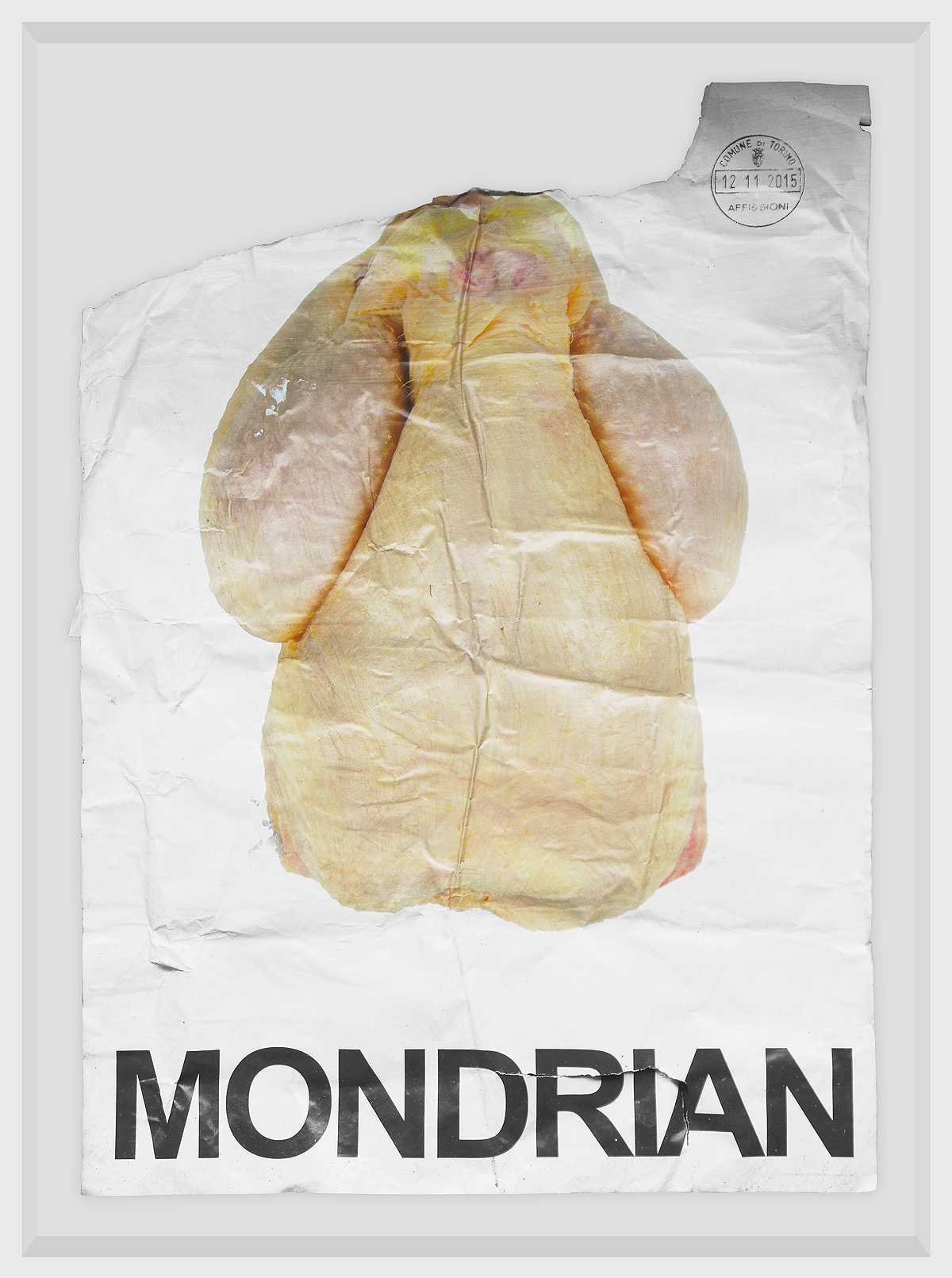

An other object on his work concerns the temporal dimension of the rent of spaces, which coincide with the same put-on-view of the operation and its adequate fruition, that means of the successive formalisation of the artefacts: the poster – or a part, a fragment of it – is ripped from the walls and presented next to its photographical documentation, well-framed on the, this time internal, walls of a gallery or an exhibit space. Buzzi announces the need to go out from the whitecube spaces and then he enters them back in conditions of normal operativity, may there be an incoherence with his original spirit and intent? In respect to this, Buzzi answers that all is considered since the conception of his first operation, that the re-placement inside the historical code of the gallery exhibition is essential part of the same strategy which lets art descending into the street, which involves the circularity of the operation and which wastes the artefact to the collectors. The artwork lives in the moment of the encounter under the sky, the rest is memory, recollection and, precisely, artefact.

This articulating and disentagling movement on the walls is accompanied by the egotic practice to define himself the real public artist. The fact is that, insisting on the operations in the public context, he has however conquered a new space for art, or better, he has renewed the sense of this public space, showing us something unconceivable and exemplar (he would say). So, the tangles of art widen, but the art is always inside the world, although it’s a bit too anonymous at a first sight, that we couldn’t go out from the art diverting our glance to the world (which actually was his first intention, a parental action to the yet historical one of the avant-garde dismantling current art) and cancel the art trying to dissolve his rules and mechanisms. About it he has a cristal conscience.

Other issue. After a chicken (The evolution of the chicken… I remember it’s of 1993), in his works the protagonist is always the artist himself. He that is present. He that shows a certainly egocentric and edonistic presence. Where does his ego finish and how much autobiographic is his work?

If we look in chronological order at the subjects characterizing his career, we will notice that, passing through a chicken body used in association with a famous brand, he has been arriving to produce images that find himself as the protagonist, precisely constituting himself as the represented transmitter. He as himself and he as other ones under false pretences. In the past he made use of artists names belonging to the now collective imagination: Picasso, Van Gogh, but also Wittgestein has called his attention, with the aim of making a reflection on the sense of value of „iconic“ images, just as screens on which he reflected a vision of the world, at times entertaining, other times allusive, other again simply aesthetic.

His visual communication, quite adopting the specific language of advertising, comes from connections, from at least strange unusual meetings between content and form. I would say it’s a dialectical procedure that lets emerge the dycotomies quote/object, quote/body, me/ body, language/body. All with a particular attention to the first perspectives and forms that make the image „dense“, almost phisical, in which we can perceive the massive presence of his body.

The problem related to the body, to the in-this-case deeply authoritarian presence, I consider it as a non-conformist projection of the idea or reproposal of the historical theme of the self-portrait.

According to Buzzi, it’s very natural to expose himself, to be an image, it’s a way of being: the body/subject is necessary because it’s a crossing point, a means towards the „operation itself“, that is the real binding agent, the mature process of the correspondence image-art-world. Anyway there are surely some rabdomantic „problems related to the body“ in its identitarian sensibility, but they aren’t so much urgent and important for him. It’s important to underline again the same structure of the put-on-view of the artwork in the urban environment, connecting it with its „presence“, that means the regularity, diffusion, quantity and repetition, rythm but also the surprise: all things that have to be considered to well interpret Buzzi’s operation, just like the attention towards the system of signs stated from his body, which here becomes the ornament of the world, the heart of the world, since it’s, according to our imagination (the appearance), a prime place of the symbolic.

Therefore we want to say that there are historical-philosophical- artistic-ethnological suggestions as well as autobiographical marks that have been inspiring him during all these years.

Buzzi is no doubt operative in the street, he is attached on the walls and he feels this presence as fundamental in the everyday reality of the common life of the polis. But, how can he build his reality of the world? Are there perhaps some political values in his put-on-discourse of an art which doesn’t conceive persuasion, considering the location, as one of its basical reasons? What do his posters bring into focus? Only himself?

I would say they want to evoke an announcement of systematic imaginative freedom and transgression, since he is the transmitter of a communication that isn’t hidden in itself, the addresse and the communication message are corresponding, and combining dialectically depending on a mytho-poetic message.

Buzzi often declares there is no polical aim in his operations, no persuasive operation. Although, for example, one of his posters concerns the „multietnic artist“, where he appears black painted in his face. Some presences could bring the viewer to such a conclusion, of a focus on sociological or socio-political problems, but this remains a viewer‘s issue, according to Buzzi, his free interpretation. His intention (action) aims to a dialectics totally included in an art discourse, a strategy that fullfills his subversive idea in the street and then it’s completed in a formalisation of the event able to enter back in the conventional circuit of art with artefacts, photographies, rips and fragments of posters telling us about that brief stage on the walls: all is obviously well-documented. In this way the image becomes narration and the presented story sets its framework in the language and its conveniently fictional trait.